Back in 2007, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs sparked a revolution in the industry of mobile computers when he announced a single device that would combine an iPod with touch controls, a mobile phone, and internet communications. However, nearly a decade before Jobs took the world by storm with his persuasive “three things” speech, a company named InfoGear gave birth to the radical idea of a phone — also called the iPhone — that could help users browse email and connect to the primitive version of the internet.

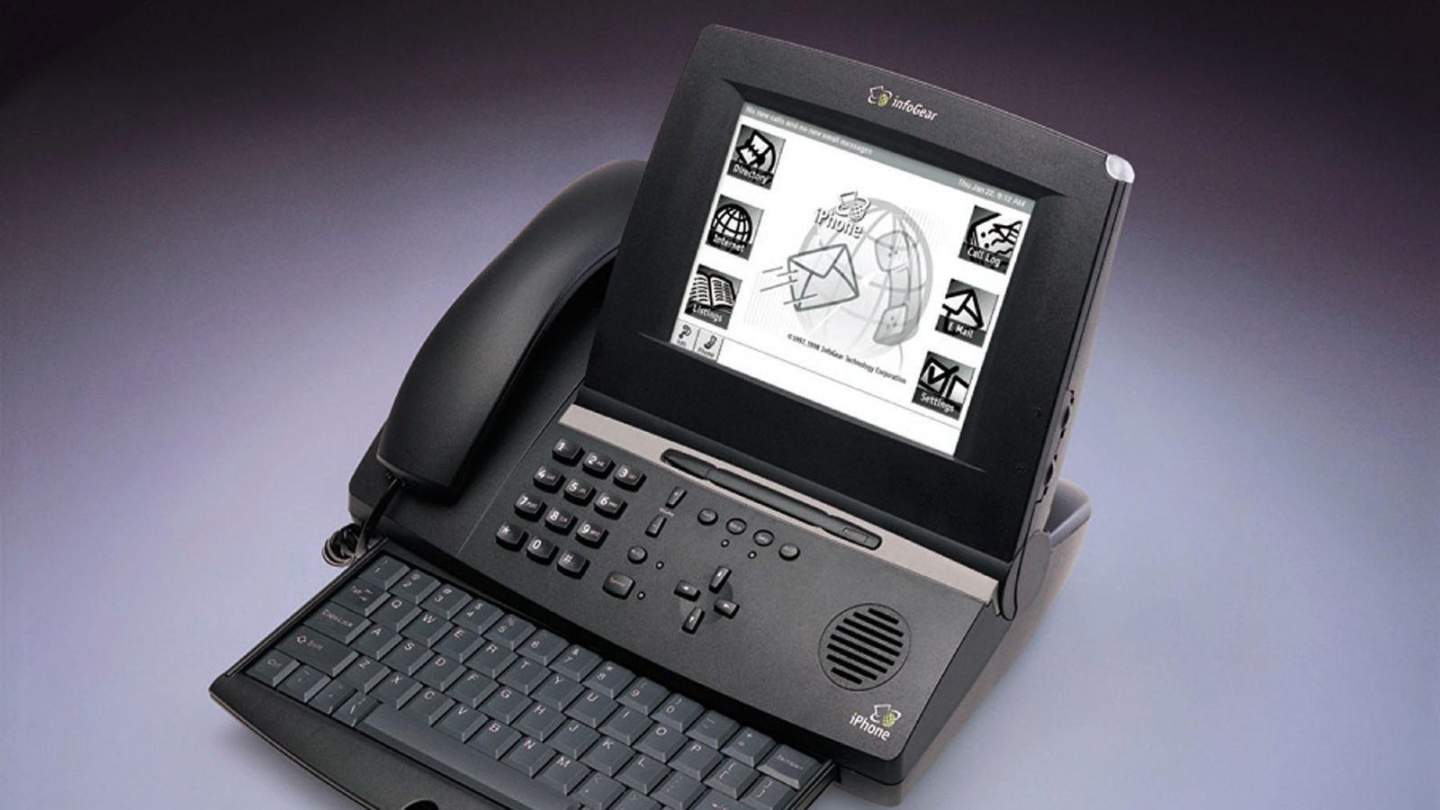

Getty Images/Getty Images

The forsaken InfoGear iPhone was born in a National Semiconductor lab as a skunkworks project, Brian McCullough writes on Internet History Podcast. The company had granted funds to engineers Chaim Bendelac, Reuven Marko, and Yuval Shahar to work on the prototype of a product that could function as both a telephone and an internet browsing device. Their first rudimentary prototype used an 8-bit processor similar to the ones found in fax machines and combined it with a screen to offer a basic web browsing experience.

‘Project Mercury’ as the future of communication

The project — called Project Mercury — was pitched to a venture capitalist, Robert Ackerman, who later explained that it didn’t take him long to realize he was looking at a device of the future. As Ackerman recounts in the Internet History Podcast interview, the unruly circuitry had him envisioning “exactly the sort of post-PC Web-based computer that Silicon Valley’s keenest minds were beginning to predict.”

Chuffed with this project, Ackerman later had to convince Gilbert Amelio, the president at National Semiconductor at the time, to relieve the three engineers and sell Project Mercury. This project group later became the standalone company InfoGear Technology Corporation.

Coincidentally, Amelio was also an Apple board member at the time and he later went on to become the CEO of Apple, where he bought Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computers and brought Jobs back to Apple as a consultant (via Wikipedia). Jobs convinced the board to oust Amelio soon after and became the CEO himself.

iPhone as the “information phone”

Mercury Project notably acquired the name iPhone in its early days of development; it was based on the techno naming fad from the early dot-com era and was used to define a telephone “on steroids.” Ackerman noted during the interview that the “iPhone” was based on the idea of an “internet phone” or “information phone.”

Ackerman wanted the InfoGear iPhone to be as easy to use as an ATM, even for seniors. His focus on simple and intuitive design led to the hiring of Frog Design, an industrial design firm that had previously designed several Mac computers. The original iPhone model came with a 7-inch black-and-white LCD touchscreen and a full slide-out keyboard. Because the LCD display alone cost $80, the first InfoGear product was launched at a price of $499 with an additional $20 charge for internet usage.

A number of features made the InfoGear iPhone a spiritual forefather to the modern smartphone. The model had capacitive touch controls to make use easy for early adopters. For instance, the iPhone automatically highlighted a phone number on a webpage, allowing users to dial it just by pressing over it. In addition, while the InfoGear gizmo was too early in its age to offer video calls or messages, it automatically transcribed voicemails with capacitive buttons on the screen to dial the caller.

Early example of cloud computing

Technically, too, the InfoGear iPhone resembled its namesake from Apple, a device that has earned appreciation from billions of users including former president Barack Obama. The InfoGear iPhone was primarily also designed to do three things — phone calls, view and reply to emails, and light web browsing. The InfoGear iPhone’s graphical interface had large icons to switch between different functions. Despite these elements, the company insisted the phone was not a replacement for the conventional PC, but rather a device that could co-exist with it.

Because the commercial version of the device only came with a single megabyte of RAM and was powered by a 16-bit processor, InfoGear did a significant part of the processing on its server, and this could very well be seen as the iron age of cloud computing. Along with these features, the device could show basic maps, give information about movie listings, and even offer content from magazines like People, Time, Money, and Sports Illustrated.

Cisco sues Apple over iPhone

Ackerman and the company wanted to develop a better device for the future with colored screens, features for video conferencing, and voice over internet protocol (or VoIP). The InfoGear iPhone 2, although missing these monumental upgrades, came with a better keyboard and a separate phone line to keep the internet connection uninterrupted. It was, by all means, ahead of its time. This is why, despite selling over a hundred thousand units over its lifetime, the InfoGear lineup failed to find its way into the homes of non-savvy consumers.

Despite its failure to appeal to a large consumer audience, the InfoGear iPhone pedigree was kept alive shortly by Cisco. Citing potential opportunities in the consumer space, Cisco acquired InfoGear in March 2000 for $300 million. After also purchasing the router-making company, Linksys, and video camera maker, Flip, in the coming years, Cisco launched Linksys-branded VoIP telephones including the 2006 mobile phone called iPhone.

The following year, Apple announced the iPhone, and that caused Cisco to sue it. The suit was eventually settled following “some classic Steve Jobs negotiating tactics,” Adam Lashinsky wrote in his book Inside Apple (via Cult of Mac). It’s more than a coincidence that Cisco’s software for the iPhone was called IOS, short for the Internet Operating System. Apple renamed its own phone software “iOS” in 2010, though the company safeguarded its trademarks before making a public announcement.

InfoGear made an iPad, too!

Incidentally, the original iPhone creator — InfoGear — had also designed a product called the iPad. Although the iPad never made it to the market as a commercial product, it was crafted to satisfy pretty much the same demand for a large personal digital assistant with a touchscreen, stylus support, rollout keyboard, and wireless connectivity. Even better, Ackerman shared some images of the prototype published over at Internet History Podcast.

Just imagine a world where Gilbert Amelio would not reinstate Steve Jobs to the Apple board, and we might have never known the iPhone as the glassy slab of semiconductors, representing luxury and filled to the brim with features — yet somehow still sporting a hideous notch!