THANKS, APPLE —

“From the get-go, this feature was useless,” researcher says of feature put into iOS 14.

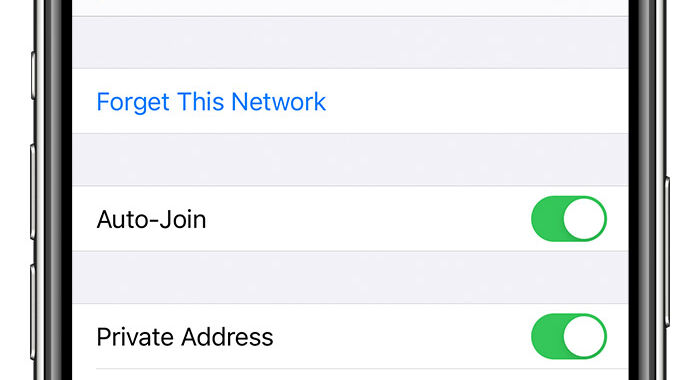

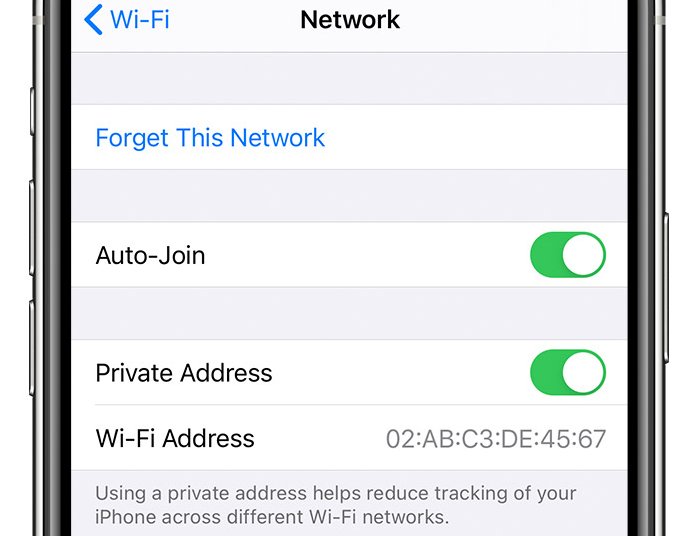

Enlarge / Private Wi-Fi address setting on an iPhone.

Apple

Three years ago, Apple introduced a privacy-enhancing feature that hid the Wi-Fi address of iPhones and iPads when they joined a network. On Wednesday, the world learned that the feature has never worked as advertised. Despite promises that this never-changing address would be hidden and replaced with a private one that was unique to each SSID, Apple devices have continued to display the real one, which in turn got broadcast to every other connected device on the network.

The problem is that a Wi-Fi media access control address—typically called a media access control address or simply a MAC—can be used to track individuals from network to network, in much the way a license plate number can be used to track a vehicle as it moves around a city. Case in point: In 2013, a researcher unveiled a proof-of-concept device that logged the MAC of all devices it came into contact with. The idea was to distribute lots of them throughout a neighborhood or city and build a profile of iPhone users, including the social media sites they visited and the many locations they visited each day.

In the decade since, HTTPS-encrypted communications have become standard, so the ability of people on the same network to monitor other people’s traffic is generally not feasible. Still, a permanent MAC provides plenty of trackability, even now.

As I wrote at the time:

Enter CreepyDOL, a low-cost, distributed network of Wi-Fi sensors that stalks people as they move about neighborhoods or even entire cities. At 4.5 inches by 3.5 inches by 1.25 inches, each node is small enough to be slipped into a wall socket at the nearby gym, cafe, or break room. And with the ability for each one to share the Internet traffic it collects with every other node, the system can assemble a detailed dossier of personal data, including the schedules, e-mail addresses, personal photos, and current or past whereabouts of the person or people it monitors.

In 2020, Apple released iOS 14 with a feature that, by default, hid Wi-Fi MACs when devices connected to a network. Instead, the device displayed what Apple called a “private Wi-Fi address” that was different for each SSID. Over time, Apple has enhanced the feature, for instance, by allowing users to assign a new private Wi-Fi address for a given SSID.

On Wednesday, Apple released iOS 17.1. Among the various fixes was a patch for a vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2023-42846, which prevented the privacy feature from working. Tommy Mysk, one of the two security researchers Apple credited with discovering and reporting the vulnerability (Talal Haj Bakry was the other), told Ars that he tested all recent iOS releases and found the flaw dates back to version 14, released in September 2020.

“From the get-go, this feature was useless because of this bug,” he said. “We couldn’t stop the devices from sending these discovery requests, even with a VPN. Even in the Lockdown Mode.”

When an iPhone or any other device joins a network, it triggers a multicast message that is sent to all other devices on the network. By necessity, this message must include a MAC. Beginning with iOS 14, this value was, by default, different for each SSID.

To the casual observer, the feature appeared to work as advertised. The “source” listed in the request was the private Wi-Fi address. Digging in a little further, however, it became clear that the real, permanent MAC was still broadcast to all other connected devices, just in a different field of the request.

Mysk published a short video showing a Mac using the Wireshark packet sniffer to monitor traffic on the local network the Mac is connected to. When an iPhone running iOS prior to version 17.1 joins, it shares its real Wi-Fi MAC on port 5353/UDP.

Upgrade to iOS 17.1 to prevent your iPhone from being tracked across Wi-Fi networks.

In fairness to Apple, the feature wasn’t useless, because it did prevent passive sniffing by devices such as the above-referended CreepyDOL. But the failure to remove the real MAC from the port 5353/UDP still meant that anyone connected to a network could pull the unique identifier with no trouble.

The fallout for most iPhone and iPad users is likely to be minimal, if at all. But for people with strict privacy threat models, the failure of these devices to hide real MACs for three years could be a real problem, particularly given Apple’s express promise that using the feature “helps reduce tracking of your iPhone across different Wi-Fi networks.”

Apple hasn’t explained how a failure as basic as this one escaped notice for so long. The advisory the company issued Wednesday said only that the fix worked by “removing the vulnerable code.”

This post has been updated to add paragraphs 3 and 11 to provide additional context.