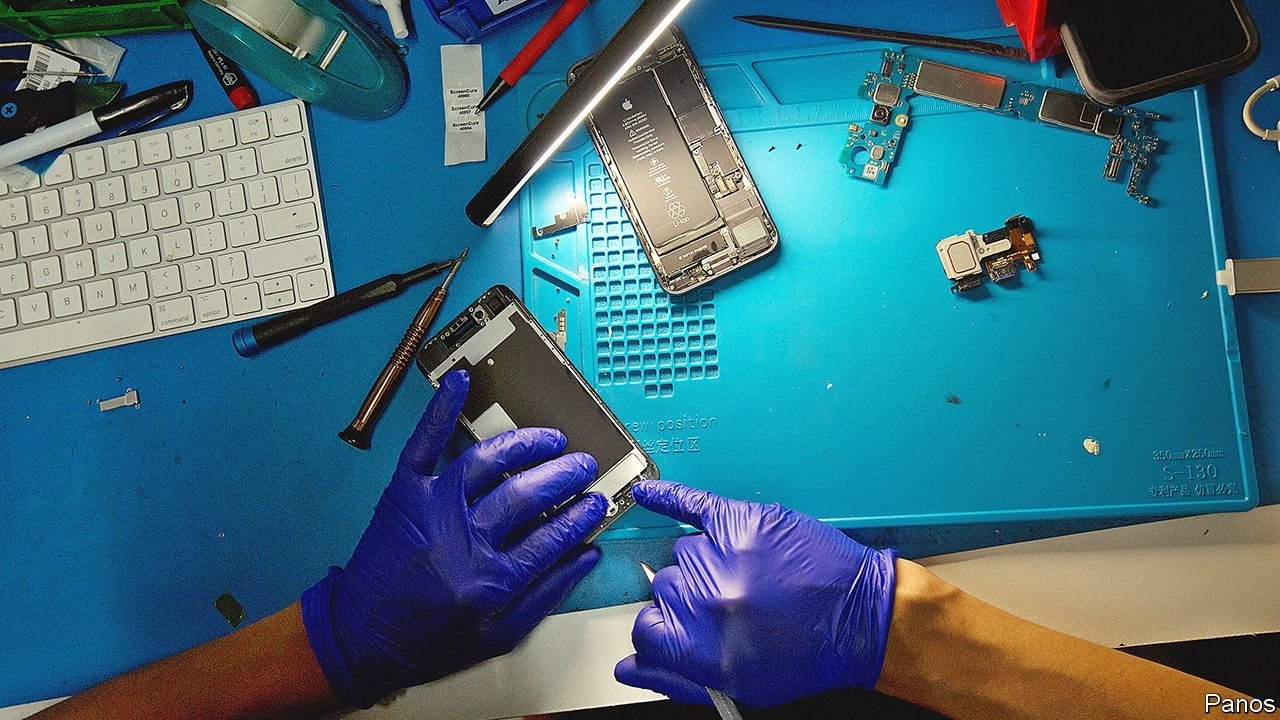

APPLE’S PURPOSE has always been to empower the users of its wares. “People are inherently creative. They will use tools in ways the toolmakers never thought possible,” once opined Steve Jobs, the computer maker’s late co-founder. So it was always odd that the firm went to great lengths to stop customers fixing its products. Repair manuals were kept secret; genuine replacement parts were hard to come by; and, most recently, replacing the screen of the latest iPhone disabled the gadget’s facial-recognition feature.

No longer. In a series of moves that surprised many, Apple earlier this month promised a software fix to make the new iPhone model more repairable, and on November 17th announced that it will allow individuals to mend their devices and provide manuals, tools and parts. Even its critics applauded, especially the leaders of a growing global “right-to-repair” movement including Kyle Wiens, the boss of iFixit, a website that sells parts and publishes free repair guides.

Yet the likely impact of the “Self Service Repair” programme is unclear. A new online store will open from early next year. Owners who return used parts for recycling will get credit toward a purchase. Independent repair shops can join in, without signing onerous agreements with Apple. And, crucially, repairs by individuals will no longer void the warranty (damage done while tinkering is not covered).

But the toolmaker is ceding less ground than first appears. Apple’s replacement parts, like its premium devices, cost a pretty penny. A new screen for the iPhone 12 is priced at $268. Nor is it clear to what extent Apple will make its devices easier to repair. Because even swapping a battery requires removing the easily breakable screen, not many will try this at home.

Still, if Apple went further, its repair programme could become a model for the smartphone and, perhaps, the wider electronics industry. Even its current form will push rival device-makers to follow suit. “When it comes to repairs, Samsung Electronics is doing even worse than Apple,” says Mr Wiens. Apple’s move, he adds, has in one fell swoop given the lie to many arguments that electronics firms use against making gadgets easier to repair, such as that people might hurt themselves.

Apple has also managed to get ahead of the regulatory trend, says Nabil Nasr of the Rochester Institute of Technology, who is working on a study for the Group of Seven (G7) wealthiest democracies about the life cycle of consumer-electronics products. Regulators, he explains, are tackling the problem of e-waste—it may soon become difficult for firms to comply with all the mandates. In America, for instance, legislatures in 27 states are now discussing right-to-repair bills. The European Union is also moving towards passing such rules.

Apple-watchers wonder if the firm will try the same strategy elsewhere in its business. It could make pre-emptive concessions, for example, in the heated controversy about how it governs the app store on the iPhone. On November 9th a federal judge in California denied Apple’s request to stay part of a recent ruling. This requires it by December 9th to allow app developers to inform their users how they can pay them directly and avoid Apple’s fees of up to 30% of the purchase price. Perhaps Apple might loosen up there, too.

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “iMac, iPhone, iRepair”